The otherworldly tension between technical and extreme altitude mountaineering mirrors that between inventing and patenting.

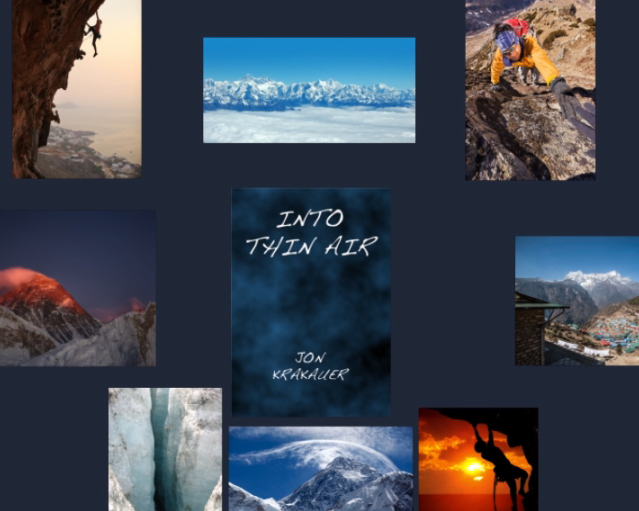

When it comes to extreme adventure, I’m strictly armchair with a seatbelt. Yet, here we are in the patent death zone. It’s no coincidence, then, that this blog is called The Vertigo Ledger, the “vertigo” being my reaction to the third rung of any stepladder, the “ledge” being, well, any ledge. As for The Inventor Sherpa Theater, that name emerged after a reading or two of Jon Krakauer’s riveting book, Into Thin Air.

Jon Krakauer Contemplates Leaping Into Thin Air

Into Thin Air* chronicles the adventures and tragedies of teams that attempted to summit Mount Everest on May 11, 1996, during which eight climbers died. Jon Krakauer had been retained by Outside Magazine to write about the commercialization of Everest. He agreed to travel to Nepal and accompany the teams on their ascent, but only on the condition that he could sign on to go all the way to the top. He didn’t think Outsider would say “yes.” But, they did.

Krakauer reflects that he had overcome quite a few of the boldest mountaineering challenges below 17,200 feet (nosebleed anyone?), yet was more than a little uneasy contemplating pressing onward and upward an additional 12,000 feet to the summit of Everest, well into the Death Zone, beginning around 26,000 feet, where the oxygen level is one-third that of sea level and even moderate storms, materializing out of nowhere, can be fatal.

In his own words, Jon describes his introduction to Everest as he peered out a window of Thai Air flight 311 soaring toward Kathmandu:

The ink-black wedge of the summit pyramid stood out in stark relief, towering over the surrounding ridges. Thrust high into the jet stream, the mountain ripped a visible gash in the 120-knot hurricane, sending forth a plume of ice crystals that tailed to the east like a long silk scarf. As I gazed across the sky at this contrail, it occurred to me that the top of Everest was precisely the same height as the pressurized jet bearing me through the heavens. That I proposed to climb to the cruising altitude of an Airbus 300 jetliner struck me, at that moment, as preposterous, or worse. My palms felt clammy.

Forty minutes later I was on the ground in Kathmandu.

Jon Krakauer was at home below 17,000 feet, where he relied on his technical skill, experience, focus, and all-in enthusiasm to propel one successful feat of mountaineering prowess after another. He wasn’t even all that interested in exploring higher altitudes, or at least not until he got the intriguing offer from Outside. Once he committed though, he started to size up the new world he was entering, a world where, yes, his skills would be indispensable, but where he would be wise to embrace new skills, where he would need to reassess his limitations, and where it would be crucial to seek out the help of others already tuned in to the secrets of reaching, surviving in, and returning from the Death Zone.

From Thin Air Into Thin Air ~ The Patent Death Zone

As I read on, the parallels between transitioning from strictly technical to super high altitude climbing and transitioning from inventing to patenting began to crystallize for me. Think about it. You might have golden hands in the lab or machine shop and killer ideas to match yet, in an instant, you could find yourself plummeting into a gaping fissure in one of your patent claims, wedged a dozen jagged rejections down a legal crevasse, air vacuumed from your arguments, your invention crushed beneath you. And, the rescue party pinned down in a blizzard of paperwork.

Even if it seems that you’ve just pulled your inventive concept out of thin air all by yourself, the odds of successfully soloing that concept into the rarified air of the patent death zone are heavily stacked against you.

That’s where the “Sherpa” part comes in. The incomparable Himalayan sherpas act as indispensable high-altitude climbing guides and provisioners, and much more. They’ve grown up at high altitude, have scampered and trudged up and down the mountains many times, and have witnessed much of the worst those peaks can dish out. So, it is the wise mountaineer who welcomes and models the wisdom, skill, situational intelligence, and conditioning of these too often unsung heroes of thin air. And, wouldn’t it be nice if we could hook our patenting lifeline to some sort of, well, Inventor Sherpa?

So, that’s it then. You may have just had an idea for an invention having nothing to do with your job or school work, or that idea may have everything to do with what you’ve been preparing for and working on for years. Or, maybe you’re working with an inventor in one or more of the other Player roles in the context of a large or small or, as yet, non-existent company. Maybe you’re in an academic setting. You may or may not already be an expert in the field of your invention. But either way, you’ve had an idea about an invention, an idea called an inventive concept, and you’d like to patent it.

If any of this feels like you, the shear magnetism of an idea is already drawing you toward an alien vista laced with encroaching unease. The universe of inventive concepts and the patent world have always existed in parallel with your daily pursuits, but now they want a piece of your crazy, busy life. And, that’s why you might want to consider hooking into a sort of collective Sherpa that’s beginning to coalesce here in the Inventor Sherpa Theater.

(*) Krakauer, J. (1997). Into Thin Air. New York, NY: Random House. [See Chapter Three, Over Northern India, March 29, 1996 * 30,000 Feet.]